Jacob Perkins, who is counted among the most successful of the International Drillers, would progress from the shaggy, awkward-looking man shown in his wedding photo in 1876 to one of the most prominent oil producers in Galicia (modern-day Poland). Little is known about Perkins prior to his wedding to Jenny Jardine of Petrolia in 1876, at which time he is listed as an oil producer, and it was most likely while living in Petrolia that Perkins became acquainted with William McGarvey, a store owner. McGarvey became interested in the oil industry and left to explore oil fields in Galicia, a province of Austria-Hungary, and recruited many oil labourers from Lambton County to help his company develop the region. Jacob Perkins' brother, Cyrus, was among the first wave of drillers to join McGarvey in 1885 and Cyrus' wife, Margaret, frequently wrote to Jenny Perkins describing their experiences.

In 1887, Jacob Perkins was hired by Bergheim and McGarvey to operate oil fields and joined the growing group of Canadian international drillers, bringing with him his wife and two children and settling in L'viv. Perkins eventually went on to own his oil fields, moving his family (including two more children who were born in Galicia) to Humniska.

The initial move to Galicia came as a shock to the family because the conditions were not what they were used to in Canada. Many of the houses offered to the International Drillers were simple thatched-roof huts with mud flooring. The women often had to shoo ducks from inside the home and cooked over open-fires. The children were quickly integrated into Austrian life when they made fast friends with the local children and picked up the language with ease, although the adults appear to have interacted with the local families with more hesitation. Wilfred Perkins, son of Jacob Perkins, described how the locals would steal "bolts, handles, screws and other devices" simply because they had a desire to steal, and not because they had any need for the items. In frustration, the International Drillers would visit the local parish priest and ask him to speak on the matter, leaving him a generous donation. On Sunday, the priest would climb the pulpit, shout to the congregation, "You thieves! You scoundrels!" and threaten that those who had stolen from the Perkins' derricks would not be offered absolution for their confession until the stolen items were returned. On Monday morning, the Perkinses would find a pile of machinery and kitchen utensils outside their door.

Although the Perkinses had been living in Galicia for 27 years by the outbreak of the First World War, they were still British citizens and, as a result, faced many difficulties caused by the Austrian government. When Britain declared war on Germany in August of 1914, the Perkinses had been having a reunion with their children. Wilfred, an instructor of languages at Coe College in Iowa, and Eddie, a student at Coe College, were home for summer vacation, and Olivia, who had married Ernest Nicklos, son of Charles Nicklos, was visiting with her children to escape the unrest in Mexico where her husband was an oil driller. As Russian troops began to invade the Galician Countryside, the women and children escaped by train to Bielitz while Jacob and his son, Herbert, remained to shut down the oil wells and left just as Russian troops could be seen on the horizon. While Wilfred and Olivia managed to travel back to the United States, Eddie was caught and detained as a prisoner of war by the Austrian government for four months to prevent him from joining the British forces. At the same time, Jacob and Jenny had travelled to Vienna where they had been placed under house arrest.

By the spring of 1915, Jacob and Jenny Perkins were able to return to their home but were still not allowed access to their oil fields due to their status as "enemy aliens". Jacob expresses his frustration and relief at being able to return to work in a letter written to his daughter, Olivia, on December 20, 1915: "I was many times afraid I would break down completely and lose my senses. Then I got permission to return to my business and pleased to inform you I am feeling first class again; very, very much better than I did in Vienna with nothing to do."

Unfortunately his relief would be short-lived. In February 1917, Perkins sold his oil shares to Vienna Floridsdorf Mineral Oil Factory Company and was to be paid 600,000 kronen once peace was declared but the Austrian mark had been so devalued that he lost most of his life's work. During the winter of 1917, he caught a cold which left him weak and died July 21 1917 of a blood clot, although Jenny Perkins said, "he died of a broken heart".

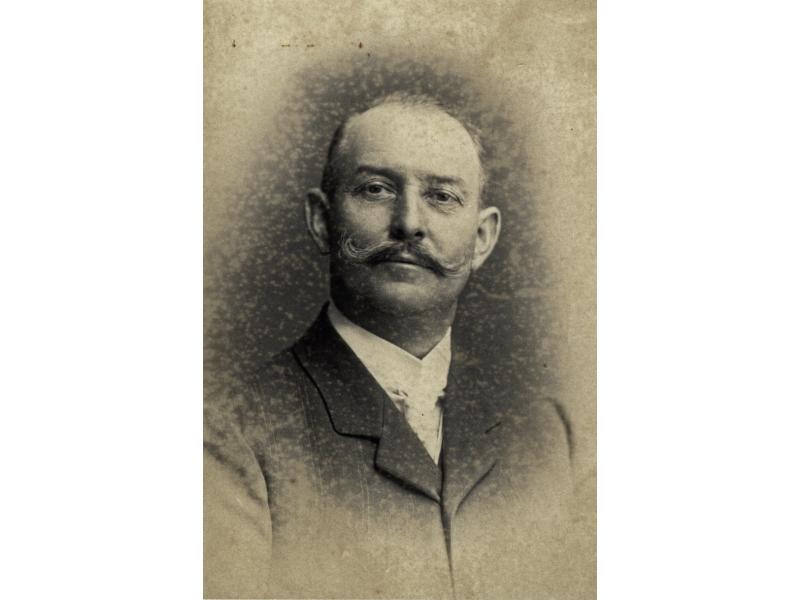

Jacob Perkins

Jacob Perkins  Jacob and Jenny Perkins, probably on their wedding day.

Jacob and Jenny Perkins, probably on their wedding day.  Perkins family in Petrolia, 1886: Jenny and Jacob with their three children, Olive (white dress), Herbert (standing), and Cyrus Wilfred "Fred" (seated, centre).

Perkins family in Petrolia, 1886: Jenny and Jacob with their three children, Olive (white dress), Herbert (standing), and Cyrus Wilfred "Fred" (seated, centre).  Perkins family in Galicia ca. 1901-1903. From left to right: Jennie, Cyrus Wilfred "Fred", Herbert, Olive, Jacob, Charlie. Seated front: Eddie.

Perkins family in Galicia ca. 1901-1903. From left to right: Jennie, Cyrus Wilfred "Fred", Herbert, Olive, Jacob, Charlie. Seated front: Eddie.

Add new comment